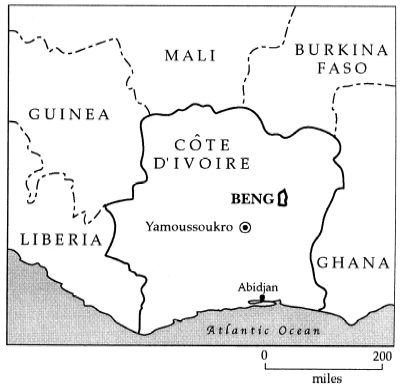

With a population of about 25,000 in the West African nation of Côte d’Ivoire, the Beng are one of the smallest and least known of some 60 ethnic groups in a nation roughly the size of New Mexico. They inhabit an ecological border zone between the rain forest to the south and savanna to the north.

The majority of Beng people still live in relatively small, rural villages, where they practice a mixed economy of farming, hunting and gathering. Both men and women work long hours in the fields much of the year; children begin training in local farming techniques from the age of two or three years old. In precolonial times, men (and some women) hunted game regularly in the forest. However, the growth of a cash economy, with its more labor-intensive farming techniques based on monoculture, has reduced the time available for hunting. Women, men, and children continue to collect wild plants (especially berries and leaves), as well as trap a variety of small forest creatures.

Beng families are usually large. In the villages, birth control efforts are limited to a taboo on sex until a new baby can walk independently. Extended families typically consist of a husband and wife (or wives), all their unmarried daughters, all their sons, and their married sons’ wives and children.

Until recently, virtually all Beng practiced their own religion, which requires people to offer prayers and sacrifices to sky/god (eci), ancestors, and a variety of bush and Earth spirits. Diviners use a variety of techniques to communicate with invisible spirits of the bush and of ancestors, and then interpret the spirits’ communications to their concerned clients. Often, the divination indicates that a sacrifice to the Earth is necessary. In this case, the client then consults an Earth priest. These priests worship the Earth spirits according to the traditional six-day Beng calendar, offering prayers on behalf of people who seek protection against witchcraft; relief from afflictions deemed to have a spiritual cause; or atonement for past sins.

Many Beng people now embrace Islam or Christianity. However, many do not so much “convert” to these new religions as add them to their spiritual practices.

The Beng have probably maintained trade relations with neighboring groups for centuries—trading kola nuts, bush meat, and bark cloth for pottery, woven cloth, and machetes.

In recent years, immigrants from the dry north have arrived to farm in Beng villages, thanks to the region’s reputation for rich soils. To ensure that their children grow up able to speak with these various migrants and traders, Beng parents teach children to become multilingual from a very early age. Increasingly, they also send their children to public schools, where they learn French from first grade on.

Sadly, the Beng way of life has been threatened by the nation’s political turmoil that began with the death in 1993 of long-time president, Houphoüet-Boigny, who left no viable succession plan in place. The lingering effects on the Beng of the country’s troubles remain to be fully documented.

The Beng Community Fund aims to improve the lives of Beng villagers. To date, most projects have emphasized clean water and educational programs.